On Wednesday, I presented at the New York State Association of Independent Schools (NYSAIS) Special Education Conference. My session was called “Access & Equity in Math Class for Students with Disabilities.” The goal of the presentation was to review the Standards for Mathematical Practice and pair great Instructional Routines with each one so that the special educators in attendance would be prepared to engage their students in this high level of mathematical thinking.

I made one major oversight in the planning of this session…I’ll let you guess what that was…

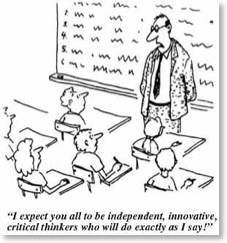

Yes, we could not review the Standards for Mathematical Practice (SMP), when only two of the participants had even heard of them prior to the session. Because of this, the goal of the session changed to using instructional routines to model what was meant by each of the Standards for Mathematical Practice.

Yes, we could not review the Standards for Mathematical Practice (SMP), when only two of the participants had even heard of them prior to the session. Because of this, the goal of the session changed to using instructional routines to model what was meant by each of the Standards for Mathematical Practice.

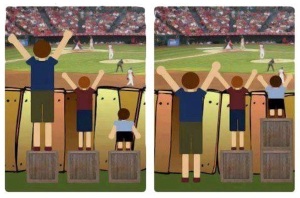

Most of the instructional routines were culled from the #MTBoS. For instance, we used I Notice/I Wonder from The Math Forum to model SMP.1 – Making sense of problems and persevere in solving them, Estimation 180 to model SMP.2 – Reason abstractly and quantitatively, and Which One Doesn’t Belong? to model SMP.3 – Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others.